History of Diamond Caverns – Jewel of Kentucky’s Underground

By Stanley D. Sides

© Diamond Caverns, LLC. 2006

In 1811 storm clouds of war with England were gathering over unresolved territorial issues from the Revolutionary War. A junction of several stagecoach roads in south central Kentucky was intersected by a road that led eight miles away to Flatt’s Cave. The British embargo of American ports led to a shortage and inflated price of saltpeter. The dry sediments in Flatt’s Cave, soon named “Mammoth Cave,” were a valued source of saltpeter (potassium nitrate), necessary for the production of gunpowder.

One and a half miles north of the road junction, named Three Forks, saltpeter was also being mined in Short Cave and nearby Long Cave, on the west side of a long deep sinkhole valley. Underneath this valley, and undiscovered at this time, was a beautiful cave that later became known as Diamond Caverns.

By 1859, Three Forks was a sleepy village with 75 inhabitants. It was universally known as Bell’s Tavern for the town’s famous hotel, and was the departure point for the eight mile trip to Mammoth Cave. Most people of means stayed at Bell’s Tavern, revered for its peach and honey brandy, and then traveled by horseback or stagecoach on the single lane rutted road to Mammoth Cave to tour the world famous attraction. One and a half miles north of Bell’s Tavern, very near the road to Mammoth Cave, a slave of landowner Jessie Coats discovered a pit in the rocky bottom of the valley on July 14, 1859. Lowered on a rope into the cave, this first visitor thought sparkling calcite formations resembled diamonds, and the name for the cave was born.

The next day, a survey team entered the cave, descending rope ladders to assess the new discovery. Steps were built into the Rotunda and beyond, and a building was constructed to protect the entrance. The cave has remained remarkably pristine because of the conservation efforts that occurred immediately after the cave was discovered.

A newspaper article in the Louisville Daily Courier from August 19, 1859 describes the discovery and early history of the cave, referring to it as “Richardson Cave,” named for one of the original explorers. After a month of work developing the cave for tours, on August 19, 1859 the Kennedy Bridal Party was the first to enjoy the newly opened show cave. Except for short periods during the Civil War, the cave has been shown as an attraction for over 163* years.

In 1854 the Louisville and Nashville Railroad reached Three Forks. A branch line was laid to the nearby town of Glasgow. Thereafter, the town was named Glasgow Junction, and much more recently, Park City. The arrival of the railroad brought many more visitors to Diamond and Mammoth Caves.

The original owner of Bell’s Tavern, William Bell, left the tavern to his son, Robert, and daughter-in-law, Maria Gorin Bell. Maria’s father, Franklin Gorin, was a Glasgow lawyer and early owner of Mammoth Cave. After Robert Bell’s death, Maria married a prominent widowed local landowner, George Proctor. In addition to running Bell’s Tavern with his wife, George showed Diamond Cave to travelers. At the same time, his brother, Larkin Proctor, managed the Mammoth Cave Hotel, and also owned the stage line that served Bell’s Tavern, Diamond Cave, and Mammoth Cave. On December 12, 1859 Maria Proctor’s uncle, Joseph Rogers Underwood, a renowned Bowling Green lawyer and senator, bought Diamond Cave and 156 acres from Jesse Coats for $1,200.00. In addition to owning the Diamond Cave property, Underwood was also the managing trustee of the Mammoth Cave Estate, responsible for making Mammoth Cave a commercial success.

The Civil War effectively shut down visitation to Diamond Cave, as well as to Mammoth Cave. Guerrilla raids, use of the railroads for military purposes, and dreadful economic conditions ended tourist travel on the roads and railroads. Cave visitation remained stagnant in an impoverished nation after the Civil War.

Expansion of the railroads following recovery from the war led to increased tourism and development of other show caves in the region. Maria Gorin Bell Proctor’s stepson, John R. Proctor, bought Diamond Cave from Joseph Rogers Underwood for $1,472.00 in 1867. John and his father, George, continued to develop the cave. Two editions of a guidebook were printed, and numerous articles were published on the cave. John R. Proctor speculated in land and failed to settle personal debts and pay taxes on his extensive land holdings. On April 21, 1879 Seth B. Shackleford purchased Diamond Cave for $1475.00 at the Edmonson County courthouse steps. Proctor moved on to a distinguished career in public service, becoming Kentucky’s state geologist and a prominent federal civil servant.

There was a close relationship between Mammoth Cave and Diamond Cave for years. Books and cave brochures would describe both caves. Beginning in 1880, the Mammoth Cave Railroad tracks were laid just west of Diamond Cave. When the line finally opened in 1886, Diamond was one of the primary stops on the railroad. Excursions were available to see Diamond and Mammoth Caves on the same day, and still return to Glasgow Junction in time to catch through trains to Louisville or Nashville. Mammoth Cave Railroad stops also served two nearby caves opened by Larkin Proctor, Long Cave, commercialized as Grand Avenue Caverns, and Proctor Cave.

On June 11, 1900 J. B. Hatcher acquired Diamond Cave from Seth Shackelford’s Estate for $500.00. Two days later, G.T. Parker bought the cave from Hatcher for the same amount. Railroad travel brought more cave visitors, but only Mammoth Cave had national fame. Louisville and Nashville Railroad owned and promoted Colossal Cave east of Mammoth Cave, but there were few visitors. Indian Cave, Grand Avenue Cave, Proctor Cave and Diamond Cave were visited by those who sought caves with stalactites, stalagmites and other cave formations. Mammoth Cave’s extensive avenues were practically devoid of cave formations. During this period visitation to landmarks in the eastern United States was declining because of the development of national parks, and the continual discovery of spectacular natural features in the American West.

Regional tourism changed abruptly in 1904 when the first automobile braved the bad roads and arrived at Mammoth Cave. After the First World War, tourism accelerated, with many visiting the Kentucky cave region. In 1921, an oil driller named George Morrison forced another entrance into Mammoth Cave. Competition between historic Mammoth Cave and Morrison’s “New Entrance to Mammoth Cave” led to vigorous competition among cave owners inciting the “cave wars” for tourists visiting the region.

During the 1920’s, as many as 17 show caves were open, including Diamond Cave. Vandalism from competitors resulted in destruction of formations in many caves, including some damage in Diamond Cave. Visitors arriving by personal automobiles on better roads also expected improved, more convenient cave trips. Electric lights were installed in Diamond Cave in 1917, using a Delco generator. In 1924, cave manager Cal Rogers replaced the original wooden staircase with a concrete staircase, and constructed the concrete bridge beyond the Rotunda around the edge of Onyx Pit.

During the 1920’s, as many as 17 show caves were open, including Diamond Cave. Vandalism from competitors resulted in destruction of formations in many caves, including some damage in Diamond Cave. Visitors arriving by personal automobiles on better roads also expected improved, more convenient cave trips. Electric lights were installed in Diamond Cave in 1917, using a Delco generator. In 1924, cave manager Cal Rogers replaced the original wooden staircase with a concrete staircase, and constructed the concrete bridge beyond the Rotunda around the edge of Onyx Pit.

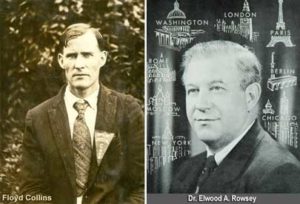

A turning point in the history of Diamond Caverns occurred February 8, 1924 when Amos Fudge, a Toledo, Ohio, businessman and his son-in-law, Reverend Elwood A. Rowsey purchased Diamond Cave from G. T. Parker for $7,000.00. Over the next 50 years the powerful personality of Dr. Rowsey, who was a Methodist minister with a doctorate in theology, elevated Diamond Cave from a local show cave into a regional feature of importance. Fudge and Rowsey sought additional investors in the cave, built cabins, enlarged the lodge, and improved the electrical system in the cave.

The death of Floyd Collins in Sand Cave in February, 1925 brought worldwide attention to Mammoth Cave and the surrounding caves. An act of Congress in 1926 authorized the establishment of Mammoth Cave National Park. The park was established in 1941 and formally dedicated in 1946.

Until 1936, Diamond Cave tours ended at the Diamond Grotto or Queen’s Den. In that year, guides discovered a continuation of the cave’s main canyon beyond the Queen’s Den, doubling the length of the visitor’s tour. More cave passages were discovered beyond Frankenstein’s Staircase, and were briefly included on the cave tour. In December, 1936 disaster struck when the lodge burned to the ground, washing extensive amounts of soot into the cave.

Click play to hear a very old recording of Dr. Rowsey’s audio introduction to the Diamond Caverns tour.

This recording is in poor condition. Much audio restoration work was done to this clip.

On September 5, 1942 Dr. Rowsey became the sole cave owner, and changed the name to Diamond Caverns. Cave explorers of the fledgling National Speleological Society organized an expedition to Diamond Caverns and surrounding caves in October, 1942. The Toledo, Ohio, cavers surveyed the cave and produced the first map incorporating discoveries made since 1936. From the 1940’s on, Dr. Rowsey and his son, Elwood (Woody), and then Dr. Rowsey’s niece, Jan Alexander McDaniel and her husband, Vernon, ran the cave property and adjoining campground through very busy years. Under Rowsey’s leadership the cave became a destination resort with hotel rooms, restaurant, and pool, in a period of nationwide expansion of campgrounds and outdoor recreation. Interstate 65 was completed through the cave region in the late 1960’s, bringing more cave visitors to the Mammoth Cave region, but also leading to motorists spending less time in the area.

Map used with permission of the National Speleological Society (caves.org)

Jan and Vernon McDaniel managed the cave and campground after Dr. Rowsey’s death in 1973. On March 20, 1976 a tornado hit the Diamond Caverns KOA Campground, Park City, and Diamond Caverns. The north portion of the Colonial Lodge was damaged and removed, leading to the current appearance of the lodge.

Moyer Enterprises purchased the Diamond Caverns Resort from the McDaniels in 1982, with ownership being later transferred to an investor group as a private membership resort. In 1993, Ronald C. Eken and his BullEk Corporation purchased Diamond Caverns Resort and a nearby public campground named Cedar Hills. BullEk purchased an adjacent eighteen hole golf course called Park Place in 1994, incorporating it into the expanding resort. Diamond Caverns received less promotion as the emphasis changed from a show cave to a large resort with many facets.

(Front row left to right) Mayo & Larry McCarty, Gordon Smith

Five cavers and their wives, Gary and Susan Berdeaux, Larry and Mayo McCarty, Roger and Carol McClure, Stanley and Kay Sides, and Gordon and Judy Smith purchased the cave property on July 7, 1999 intent on enhancing the cave as a historic commercial attraction and developing a national museum for the show cave industry. After an owners’ meeting three months later, Stanley Sides and Gordon Smith began removing rocks from a crevice in the backyard. The bottom fell out to subsequently reveal a shaft leading to 250 feet of cave passages not yet connected to Diamond Caverns. The next day, October 9, 1999 Cave Research Foundation cavers Dave West, Karen Willmes, Joyce Hoffmaster and Joanne Jones enlarged a low crawlway dig Gary Berdeaux and Gordon Smith had begun under Diamond Cavern’s Rotunda room. Three hours of claustrophobic digging in a constricted crawlway resulted in the discovery of several hundred feet of beautifully decorated virgin passages including the largest room yet found in Diamond Caverns. This New Discovery remains undeveloped and pristine with restricted access.

Five cavers and their wives, Gary and Susan Berdeaux, Larry and Mayo McCarty, Roger and Carol McClure, Stanley and Kay Sides, and Gordon and Judy Smith purchased the cave property on July 7, 1999 intent on enhancing the cave as a historic commercial attraction and developing a national museum for the show cave industry. After an owners’ meeting three months later, Stanley Sides and Gordon Smith began removing rocks from a crevice in the backyard. The bottom fell out to subsequently reveal a shaft leading to 250 feet of cave passages not yet connected to Diamond Caverns. The next day, October 9, 1999 Cave Research Foundation cavers Dave West, Karen Willmes, Joyce Hoffmaster and Joanne Jones enlarged a low crawlway dig Gary Berdeaux and Gordon Smith had begun under Diamond Cavern’s Rotunda room. Three hours of claustrophobic digging in a constricted crawlway resulted in the discovery of several hundred feet of beautifully decorated virgin passages including the largest room yet found in Diamond Caverns. This New Discovery remains undeveloped and pristine with restricted access.

Today, historic Diamond Caverns is the second oldest show cave in the Central Kentucky Cave Region, and fourth oldest operating commercial cave in the United States. The passages have been altered little despite a rich one hundred sixty year history of visitors enjoying the best decorated show cave in the State of Kentucky. Diamond Caverns is within the Mammoth Cave Area International Biosphere Reserve and is surrounded by Mammoth Cave National Park, a World Heritage Site.

Suggested reading:

Gorin, Franklin. The Times of Long Ago. John P. Morton and Company, Louisville, 1929. Bicentennial Edition Reprint, 1992. 142 pp.

Kieth, Jean E. “Joseph Rogers Underwood—Friend of African Colonization.” Filson Club History Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 2, April, 1948, pp. 117-132.

Priest, Nancy L. “Joseph Rogers Underwood: Nineteenth Century Kentucky Orator.” The Register, Kentucky Historical Society, October, 1977, pp. 79-97.

Ward, L.E., “A Subterranean Adventure in Diamond Caverns.” Bulletin Number Six of the National Speleological Society, July, 1944, pp. 6-24, 37.

Ward, L.E., “More Subterranean Adventures.” Bulletin Number Seven of the National Speleological Society, December, 1945, pp. 19-33, 56.

Wright, Charles W. Guidebook for the Diamond Cave. Charles G. Smith, Printer, Glasgow, Ky, 1860. 16pp.